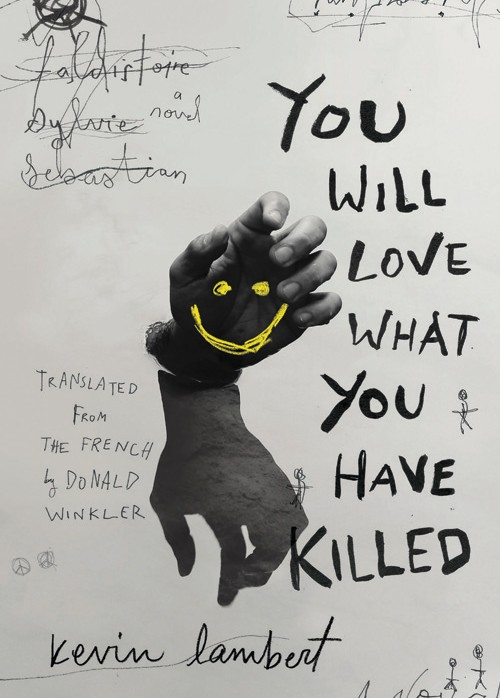

You Will Love What You Have Killed by Kevin Lambert

You Will Love What You Have Killed

by Kevin Lambert

translated by Donald Winkler

Biblioasis, 2020; 185 pages; $19.95

review by Patrick Mackenzie

The narrative terrain of You Will Love What You Have Killed is, to put it mildly, unstable. Cold, damp, toxic, slippery, are adjectives that could also be used to describe the rhetorical landscape that constructs Kevin Lambert’s unnerving and phantasmagorical novel. The terrain we are speaking of here is that of Chicoutimi, a borough of the city of Saguenay, Quebec; and the first-person narrator of the novel, Faldistoire, an unreliable narrator if there ever was one, has a seriously pathological hate-on for his home-town: “I scan the skies for the best way to damn Chicoutimi, I want to know you utterly, to master every facet of this landscape I despise. I yearn to see you laid waste. I long to witness your death throes, to see your helpless eyes begging for mercy.” As it turns out, Faldistoire’s hatred is justified, for Chicoutimi is a town of secrets, a town that kills its own children. But these dead children have an uncanny ability to return from the grave and trouble the inhabitants of the town that killed them.

In the second chapter, Faldistoire, “. . . the name my mother gave me for some still-obscure reason that I’ve been pondering for a while now, seeking a buried meaning, perhaps one that doesn’t exist,” offers the reader a description of the “Commercial Advantages” of Chicoutimi. The account reads like a tourist pamphlet written at the behest of the local chamber of commerce: “You can find everything in Chicoutimi, whatever you want you can get at place du Royanne, at Walmart, or at the big Canadian Tire, or at Club price . . . ” Note the specificity of the retail landscape. In a synecdochal maneuver, Chicoutimi becomes representative of the greater North American, neo-liberal, late capitalist order of which it is necessarily a part — a society ruled by idiocy and hypocrisy, and one that willingly sacrifices its children, symbolic of a livable future, to the gods of crass consumerism. Witness the horrific death of young Sylvie, reduced to ground meat by a giant snowblower while tunnelling in a pile of snow: “The blower spits out a brief jet of scarlet snow, with Sylvie pulverized inside it, onto the snow bank.” Then there’s the death of young Croustine, eaten alive by two cougars after falling, or was he pushed, into their enclosure at the Chicoutimi zoo. Whether or not these deaths are actual murders or merely accidents is never made clear, but the effect is to suggest that something both systematic and indifferent is responsible — such as an entire economic and social order.

As it turns out, however, this economic order will not stand: “All of Chicoutimi’s structures were built over a fault patched up with concrete and asphalt. A long, hidden fault, a flaw the inhabitants ignored, they never knew how to value the beauty of such a rupture.” The inevitability of collapse is hastened by Chicoutimi’s dead children returning from the grave to exact revenge on their parents and teachers for allowing them to be sacrificed to an indifferent economic system. “Chicoutimi shakes when the first bomb explodes. My magnificent friends, my dead children, are blowing themselves up at the four corners of the city . . . Chicoutimi rumbled seven times, great faults split the ground, and the deeps from nowhere start to engulf its hideous suburbs.”

This novel could have easily been titled You Will Kill What You Have Loved, for the author seems to be suggesting that our current modus operandi is no longer working — if it ever really worked at all — and we are witnessing its inevitable breakdown; but it is children, symbolic of the most vulnerable among us who will bear the brunt the collapse. You have been warned.