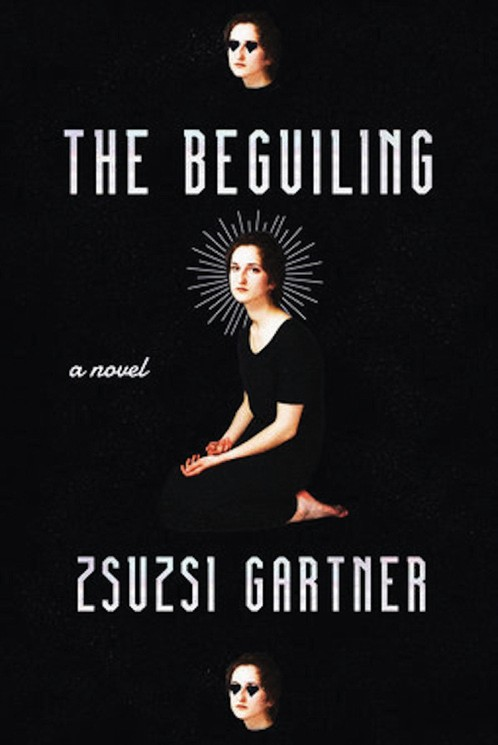

The Beguiling by Zsuzsi Gartner

The Beguiling

by Zsusi Gartner

Hamish Hamilton, 2020; 288 pages; $29.95

Review by Peter Babiak

St. Augustine is, without question, the most intriguing saint. I learned nothing about him from our parish priest, but had to wait until university, where my Rhetoric professor — a cerebral Jesuit at St. Jerome’s College — confounded us by saying Augustine revered rhetoric more than God but that this wasn’t such a big deal because they were both kind of the same thing. What he meant, I think, is that instead of thinking that meaning, or whatever it is we think we’re communicating when we speak or write, exists in some immoveable spot outside of language, we should try to wrap our minds around the possibility that everything under the stars, and everything above them too, is a divine fabrication of language. My mind kept coming back to this chestnut as I read Zsuzsi Gartner’s The Beguiling, a sublimely choreographed scattershot of episodic vignettes that resolve themselves, with a dexterity and finesse I’d only call “classical,” into a picaresque novel commanded by a magnetic narrator.

That narrator, Lucy, after the unusual death of her film-buff cousin, Zoltán, realizes she’s “been unconsciously jonesing for what I’d come to think of as the tellings.” Confessions, in other words. They — strangers — start confessing to her; thirteen of them, in thirteen chapters, like Augustine’s salacious and celestial Confessions. Seemingly out of the blue — over the counter at Kinko’s, on the street, over fences, at a bar — and as we read, which always involves a modicum of beguiling, we start fitting the pieces of the puzzle together. The first “telling” is at Kinkos after midnight, where Lucy hears the story of Arvo Pekka, the enigmatic Finn “sandblasted by love.” The rest unfold from there, though Lucy doesn’t ever say anything to her confessants afterwards, choosing to let them “drift away like candle smoke,” and with each telling we progressively wonder if, rather than pieces of one puzzle, Lucy’s magic realist quality isn’t the only bonding agent in the novel. And we’re never sure.

The “tellings,” which are as diverse in theme as they are in presentation, are eminently readable and excellent, rendered even more excellent by Gartner’s seasoned understanding of how words and sentences work themselves into narrative art. The draw, for me, is in the evocative and mind-blowingly apt elementary particles of her language, namely the metaphors and similes — to say nothing of the intelligent allusions and witty cultural references. I haven’t underlined, circled, annotated (in pen!) a hardcover novel like this in years. Dieter, a character in the telling of a woman Lucy met at the Templeton dog park, is “mad for the girls”: “They walk so languidly sometimes they don’t even appear to be moving at all. It’s as if they lack a skeletal structure, all bendy — living, breathing Gumbys and pokeys.” The actress who, while drinking at Zawa on The Drive, confesses that she faked cancer, explains to Lucy her fascination with the “sublime dialects” of medical language: “So much Latin! So much Greek!” The stories, of course, are wonderful, but Gartner’s figurations are sublime.

I haven’t read a novel like this in some time. unhampered by the compulsion to keep her story too unchallenging, Gartner is refreshingly bound by the conviction that artful stories, because they require effort on the part of the writer, should enable at least a conscientious effort on the part of readers. With its balance of entertainment and literary craft, The Beguiling reminded me, at various moments, of novels that have left me similarly exhilarated and staggered, as though I’ve just fallen in love with words all over again — Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49, Saramago’s Gospel According to Jesus Christ. Like them, Gartner’s compels us to the joys and gravities of reading.