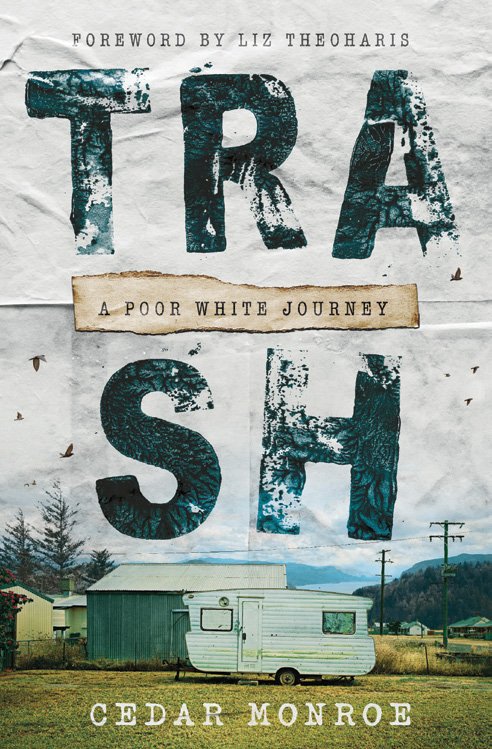

Trash: A Poor White Journey by Cedar Monroe

Trash: A Poor White Journey

by Cedar Monroe

Broadleaf Books, 2024; 231 pages; $28.99

Reviewed by Patrick Mackenzie

In an infamous quote accurately attributed to Lyndon b. Johnson in Tennessee sometime in 1964 after the president’s retinue came across a group of white southerners carrying placards of an ugly racist description, the complicated if not compromised thirty-sixth president of the united States said, “I’ll tell you what’s at the bottom of it. . . If you can convince the lowest white man that he’s better than the best coloured man, he won’t notice you’re picking his pocket. Hell, give him somebody to look down on and he’ll empty his pockets for you.”

Whether or not LBJ’s observation holds true sixty years later in our moment of political despair, what this quote is identifying is a predictable divide and conquer strategy. In the words of George Carlin spoken closer to our own dysfunctional and desperate political epoch, “That’s the way the ruling class operates in any society: they try to divide the rest of the people; they keep the lower and the middle classes fighting with each other so that they, the rich, can run off with all the fucking money.”

In Trash: A Poor White Journey, racism in general, and white supremacy specifically, are central components in the maintenance and upholding of good ol’ American capitalism. Early on, author Cedar Monroe, an Episcopal minister whose documentary-style writing centres around Abrerdeen, Washington and the dismissed and diminished inhabitants she cares for, lays down some pretty harrowing statistics embedded in a series of questions: “Why are poor white people pitted against people of color? Why are 33 percent of white people poor, and why are 43.5 percent of Americans poor? And why don’t we join forces across various divisions — and across the globe — to end our poverty?” The answer lies in the seemingly intractable place white supremacy holds in American society — as well as other parts of the world, Canada included.

The author convincingly argues white supremacy is essentially a cynical political tactic reliably employed since at least the end of the civil war. Monroe writes: “White supremacy teaches white people that they are superior to people of other races and have a special duty to rule and subjugate the world. It provides the motivation for poor white people to uphold capitalism and carries in it a continued promise of jobs and land if they comply.” of course the promises of preferential treatment, the promise of jobs (“We’re bringing back coal” — remember that guarantee offered up by Trump to unemployed, among others, Appalachians at one of his exorbitant yet somehow boring and tedious rallies?), and land under white supremacy are ephemeral at best for poor white people.

For anyone who’s been paying attention — in North America at least that’s far too few — Monroe’s citing of history and statistics will be superfluous. The writing is at its strongest and most compelling when the author is documenting the daily struggles of Aberdeen’s poor and discarded.

I’m not sure to what extent white supremacy motivates white people to cleave to a political and economic system that exploits and disenfranchises them as much as their black and brown brothers and sisters, but there’s a sense in Monroe’s story that exploitation based on ethnicity might be breaking down. In a conversation with a young white man who works seasonally in the fishing industry but was resentful of Indigenous people receiving tribal treaty rights to fish, rather than admonishing him for his resentment she asked, “‘I wonder what it would be like for you to get what you needed, just because you were alive and deserved to be cared for’. . . He stopped short, and we were both quiet for a moment. ‘Yeah,’ he said. ‘That would be cool.’”