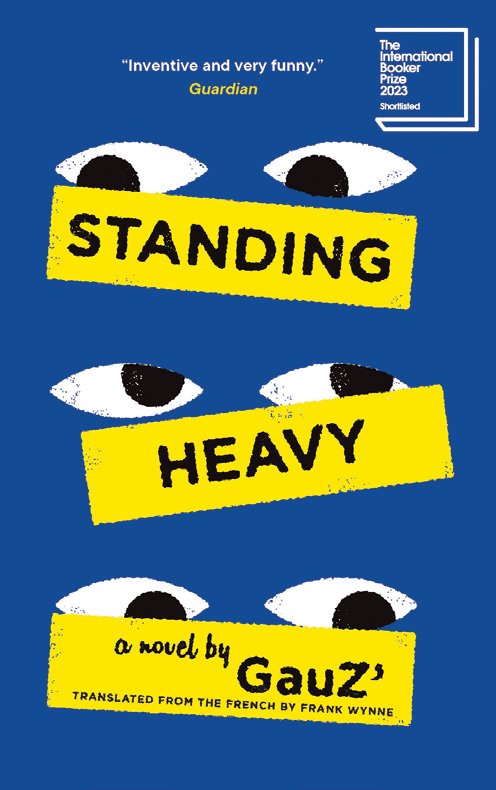

Standing Heavy by GauZ’

Standing Heavy

by GauZ’, translated by Frank Wynne

Biblioasis; 167 pages; $22.95

Reviewed by Marion Benkaiouche

Standing Heavy, initially released in 2014 as Debout-Payé in its original French, is as much a story about standing as it is about moving — through retail shops, across patrol grounds, through Paris, and across the Mediterranean Sea that separates the other ex-French. Alternating between listicles, field jottings and straightforward narratives, the story starts in an anonymous Parisian building, and takes you on a flâneur’s journey through the lives of its many protagonists, many unnamed. We start with Kassoum and Ossiri, evicted residents of a student dorm occupied by nary a student. They have just moved to the Chapel, a residence above a nightclub. Kassoum, a black boy from Côte d’Ivoire, saves a drunk white girl from Normandy. The reader feels their anxiety, as Kassoum brings Amélie to their apartment to sober up. Kassoum has never seen eyes this colour.

Ossiri goes to work at French retailer Camaïeu as a security guard, and we embark on new journeys, turning back time to the 1980s, through the evolution of surveillance to the post-9/11 new world order. When we meet Kassoum again, he now mans the security check-in for a biomedical enterprise. It is his last day of work — Amélie is pregnant. He is no longer just landed, finding his footing: he has made a life for himself.

In late 2023, Standing Heavy was released in English by Biblioasis. The story follows the “debout-payés” — those who are paid to stand and surveil Parisian businesses and retail shops, from the 1990s to the early-aughts.

GauZ’, also known as Armand Patrick Gbaka-Brédé, is witty, sardonic, and insightful. By recounting the stories and observations of black African security guards, GauZ’ weaves a postcolonial tale: he explores the means through which ex-colonial subjects across Africa find their ways to the French mainland; the means through which human resources were used to extract capital from colonial lands through enslavement and extermination, to the contemporary age where these now “liberated” human resources are used to monitor the flow of goods through French cosmetic multinational Sephora, ensuring capital is extracted from each perfume bottle or lipstick tube rather than finagled out of the store in a pair of jeans or makeshift Faraday cage.

Alternating from jotting to narrative, GauZ’ emulates the security guard’s shifts: on-shift, you must stay alert — can’t have your head down for too long. The security guards’ observations are means of surveillance, not an ethnographer’s journey in the field. The security guard must be constantly vigilant, despite the overall tedium and inaction that surveillance entails. Ethnicity, country of origin and melanin levels are poked, prodded, mocked and interrogated. GauZ’s book dances around what he terms the PSG theory: pigmentation of the skin, Social status, and Geography (PSG): “in Paris, elevated levels of melanin are correlated to a particular predisposition towards the security professions.”

The security guard is a little bit of an uncle Tom, a “Floko”, and a man looking to make a living in a complex, globalized society. While certainly sardonic and satirical, Gauz’s observations about shoppers are also touching.

In the late-aughts, my older sister moved back to Paris; a return of sorts. My Franco-Algerian family left France in the early nineties. My parents grew up in the banlieues, and emigrated shortly after I was born to evade the open-air prisons of the mind. In her twenties, my sister moved to study at the prestigious Sciences Po. on the phone, she regaled me with stories of getting ready for a night out by visiting Sephora, buying club attire at Camaïeu and H&M. These jottings took me back to those happy phone calls.