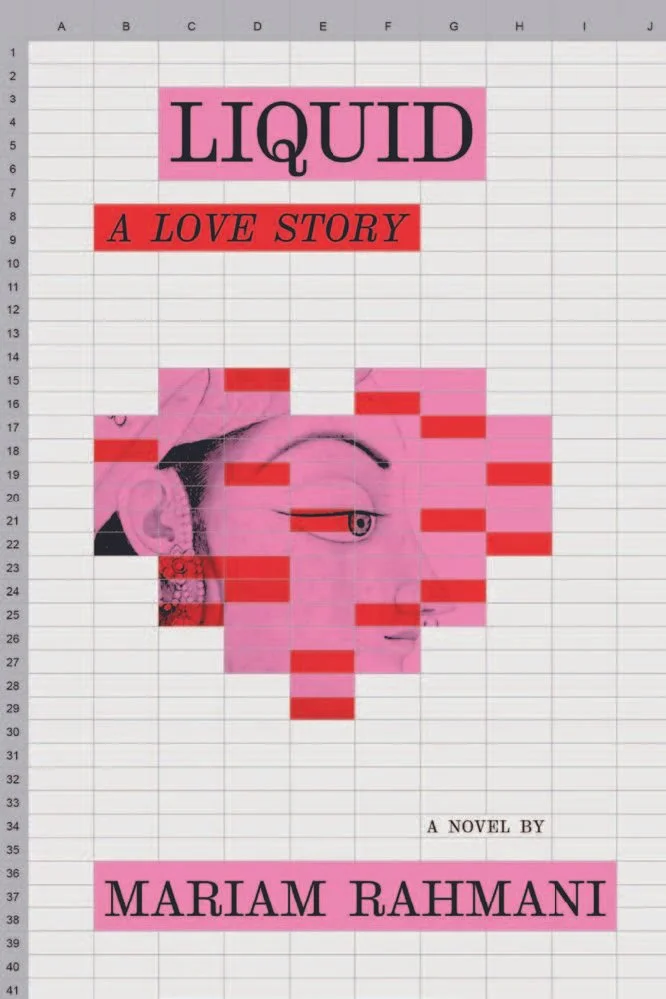

Liquid: A Love Story

Liquid:

A Love Story

By Mariam Rahmani

Algonquin Press, 2025; 306 pages; $38

Reviewed by Jessica Poon

I was thirty, experiencing the ample pecuniary challenges of existing in Toronto, when my thesis supervisor, completely sincerely, reassured me I was still nubile enough to be a sugar baby. I did not, for better or worse, explore this as a method of paying rent — maybe I should have. In Liquid by Mariam Rahmani, the unnamed, queer Iranian-Indian protagonist is counting on being hired for a summer teaching job to pay rent in Los Angeles. When the protagonist remains jobless for the summer, she becomes desperate. And so, she does what any educated, unemployed woman unable to pay rent might do — she decides the solution is to marry rich. First step? A hundred dates.

The protagonist’s best friend, Adam, is a Jewish project manager and a poet. Adam has an on-and-off relationship with Julia, a mixed race, white-presenting visual artist with a long-time predilection for infidelity. Adam is not supportive of the protagonist’s ambitions. Her dates include a guileless, legitimately nice man who, she realizes “wasn’t working working-class cosplay. He was working class.” There’s a married man — conveniently disclosing his marriage only on the date — who suggests a place that serves $37 saffron tea with barely discernible saffron. There’s Leila, a wealthy, talented sculptor who compliments the colour of her skin. She dates no fewer than three Bryans. She becomes a connoisseur of other people’s desires, while remaining academically skeptical of companionate marriage. She theorizes that the phenomenon of friends becoming lovers — for instance, in When Harry Met Sally — is, counterintuitively, similar to an arranged marriage, insofar that endogamy is typically involved, e.g. attending the same Ivy League school. Anyone who has ever dated will find numerous comical gems and absurdities.

The protagonist is exceedingly self-aware, frequently defensive, and wryly funny. For instance: “What little I gleaned only depressed me more: exercise, exercise, exercise. I both didn’t like running and already regularly went running. This was me on endorphins.” Reflecting on her mother’s thesis on Jane Austen, she says: “As with any scholarly to me, you didn’t need to read past page two.” At a party, she notices a seemingly unattended baby and notes: “There wasn’t a woman in sight and the men were too unkempt to be gay — where was its mother?” She restlessly observes who has money and who doesn’t and notes who will inherit property; as a former scholarship student, it’s a habitual fascination. She observes that wealthy Americans keep their “independent wealth as closeted as gays under the Third Reich.”

The novel is split between Los Angeles and Tehran, where the protagonist travels when her father has a heart attack. In Tehran, chapters become shorter, sometimes a single page with negative space, in a fashion reminiscent of Family Meal by Bryan Washington. Pomegranate trees are invoked often. She compares being her parents’ daughter to being an “over-wrought symbol.” Eventually, her mother pays her rent, though not without bringing up the protagonist’s lack of a husband. Their relationship is one of the funniest in the book, with her mother’s affection taking the form of criticism.

The route to love is often maddeningly circuitous, or entirely elusive. In the words of Molly from HBO’s Insecure: “Sometimes you gotta fuck a lot of frogs to get a good frog.” As the protagonist approaches her hundredth date, it becomes readily apparent who, and what, she really wants, underneath that cynicism. I have long thought of myself as too romantically scarred to have any appetite for happily ever afters, but increasingly, I’m coming around to realize, reluctantly, that I am a sucker when the writing is this good. Fans of Christine Smallwood’s The Life of the Mind and Elif Batuman’s The Idiot will feast on this novel.