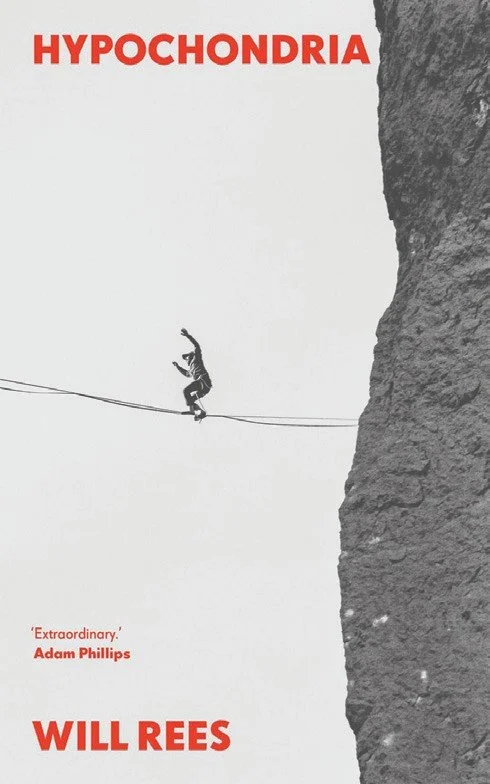

Hypochondria

Hypochondria

by Will Rees

Coach House, 2025; 230 pages; $24.95

Reviewed by Kristina Rothstein

Within five minutes of picking up Hypochondria by Will Rees, I was convinced that a multitude of my seemingly minor physical symptoms were, in fact, signs of serious or terminal symptoms believed to be caused by “nerves,” while in Hippocratic medicine it referred to an imbalance of the humours, specifically black bile. Recently, hypochondria is a label frequently affixed to women and people of colour, often because illnesses which affect them receive less funding and less study. In keeping with contemporary trends, it is not a surprise that a current theory perceives hypochondria as the result of a chemical imbalance in the brain. Hypochondria, Rees demonstrates, “always speaks to the current position of medical knowledge.” What began as a scholarly project for Rees became derailed by the gaps and absences in knowledge, the fluidity of definitions over the centuries, and the author’s own experiences with unknown illness.

These strands are all entwined in this genre-busting book, which combines history, memoir, philosophical treatise, and literary criticism. The journey through the limits of medicine is meandering and burns with intensity and frustration. Some of Rees’s guides include philosophers and writers like Kant, boswell, Kafka, and Sontag. The book is witty and nimble, pivoting from modern science to personal psychology and literature, finding connections and fusing them in unexpected ways.

In the past, the body was a closed and mysterious system, but now we can look inside, searching for revelations, and often turning up unexpected and unwelcome results in the process. In a way, worrying about what is or is not happening inside our bodies (and the quest for answers in the face of symptoms which may be illusions), questions the very stability of reality. We cling to a belief that medical knowledge has uncovered real and discrete conditions, rather than just useful methods to organize and categorize symptoms. The changing landscape of death in the West means we increasingly die less often from infectious diseases with obvious symptoms and more often from the slow deterioration of cancer and dementia. In the case of these more invisible diseases, ignorance can literally kill, which explains the obsession to know “the truth” of what is happening inside our bodies.

The narrative comes to a climax with a real trip to the emergency room and stint at the Medical Assessment Centre, where a team attempts to decode Rees’s body. He is thrilled to be delivered from ignorance, to stop trying to narrate his story to doctors in the correct way, to sit back and be a patient. In a bit of an unfair ruse, Rees does get a diagnosis of glandular fever, but there is a hint that a more serious illness (lymphoma) was missed, and has also been obscured from the story. Whatever the case, Rees’s understanding of the state of “being healthy” has been ruptured forever. This is a complex and nuanced philosophical exploration through knowledge and doubt, health and illness. It can be dense and academic at times, but it is full of insight, humour, and gravitas.