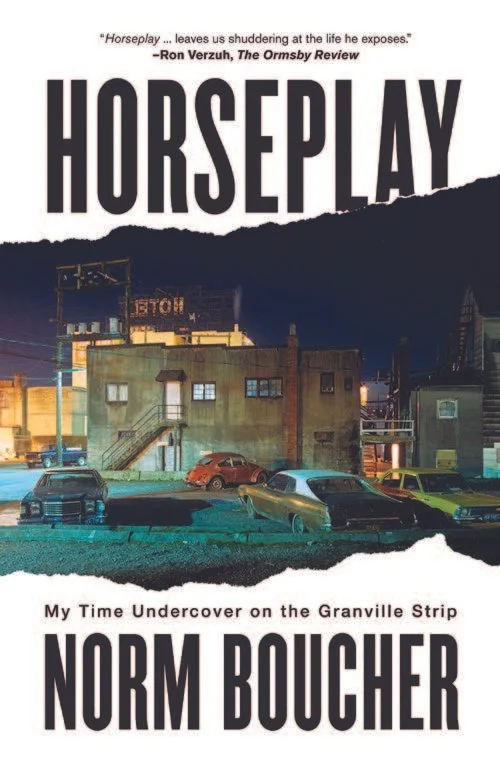

Horseplay: My Time Undercover on the Granville Strip

Horseplay: My Time Undercover on the Granville Strip

by Norm Boucher

NeWest Press, 2020; 280 pages; $21.95

Reviewed by Marion Benkaiouche

Horseplay is Norm boucher’s memoir of his time undercover on the Granville Strip, tasked with busting heroin dealers in the City of Vancouver. Boucher’s cover is a drug dealer with a minor heroin habit, ostensibly trying to score a large enough cache of the drug to sell “up North.” The goal is to identify the major heroin suppliers.

Boucher writes with a certain restraint; he catches himself thinking about the circumstances of those around him, but doesn’t let himself wander too long in the wondering. The style is fresh, full of sensual details. The reader feels the ennui and despair that begin to make their way over him as he witnesses casual violence and self-medication. But again — he doesn’t let himself think too much about peoples’ circumstances, and it’s difficult to understand whether this is a deliberate, literary style, or an absence of critical reflection upon the societal forces and histories that are unfolding before him.

The memoir has a distinctly noir aesthetic; it is slick, and that slickness renders over the plot a vague indeterminacy. Like an ethnographer, Norm needs to ingrain himself without becoming too close. Unlike an ethnographer, Norm is not overly interested in the personal details or complexities of these peoples’ lives, of what brought them to addiction or the Strip. He’s got a goal: find out who the suppliers are.

There is an animalistic, antagonistic one-up-manship, wherein he is constantly re-evaluating his place as someone not to be messed with, and someone who can be trusted. Within toxic masculinity, people have little interest in seeing the man; men, while occupying a privileged place, also occupy a place where they cannot control their own identity. The people around them project upon them an archetype. As an undercover agent, he plays with this aspect of manhood to ingratiate himself into a new crowd. He dresses the part, adopts the mannerisms of the other young men; and while there is always some distrust between Boucher and the people he meets, there is enough projected onto him to get him close to some of the bigger dealers, enough for him to complete his mission.

Initially, he is rigidly against knowing the characters’ backgrounds and personal histories. Over the eight months, tragic details of their lives, or casual mentions of their ethnic origin — Asian, Indigenous — become more frequent. The initial dissatisfaction I felt at the lack of historical context begins to seem deliberate, artistic. I feel a strong empathy to Boucher’s journey, which seems to end in a degree of ambiguity, despair, and anomie. He has spent almost a year in an environment of casual violence and casual community as an outsider-insider. There are no satisfying answers or resolutions to the drug crisis. People use drugs for fun, as a way of enacting community, to self-medicate.

The weightless equivocal tone of the writing, entertaining and readable, become bothersome over time. The author describes vividly some of the bleak realities we still encounter today; yet not once does he mention residential schools. He pokes at the edges of gendered and sexualized violence without probing too deeply. The last residential school closed in the nineties; writing from 1983, Boucher is surrounded by survivors of these schools, by those who were separated from their families in the Sixties Scoop, and by those who were raised through intergenerational trauma.

The conclusion leaves much to be desired, though I appreciate its humility. Rather than making societal pronouncements, Boucher reflects on his own drug habit: his use of alcohol to bond with other police officers after a hard day, the quiet lack of criticism around high-functioning alcoholism. Unfortunately, Boucher fails to reflect on his own role as a police officer within his society, and the uneven effects of policing on particular communities. By failing to address these contexts, this promising work of literature falls short of its own potential.