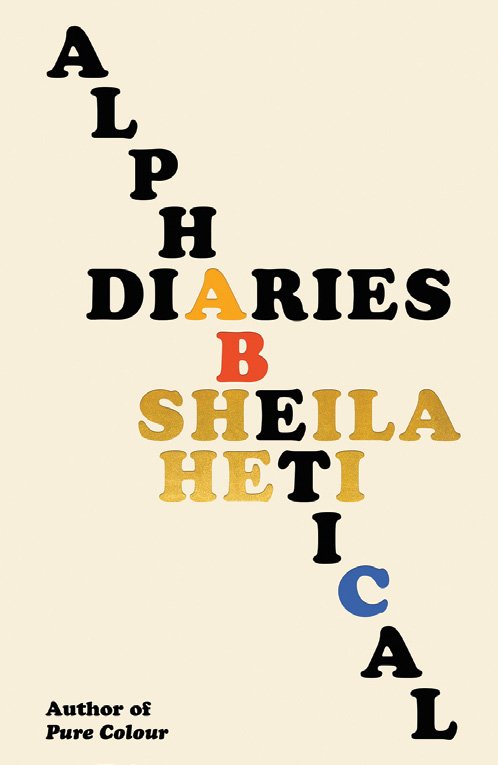

Alphabetical Diaries by Sheila Heti

Alphabetical Diaries

by Sheila Heti

Knopf Canada, 2024; 224 pages; $32.95

Reviewed by Jessica Poon

I’ve never met Sheila Heti, but after reading Alphabetical Diaries, I suspect she knows what’s inside my fridge, my moon sign, and the most well-concealed, cringey depths of my heart. It’s as if you caught someone making funny faces in the mirror and instead of being embarrassed, they looked right back at you, as though to say: I know you also do this. My friend’s sister has a ring with “Cunt Power” inscribed on the inside and I’m tempted to describe Alphabetical Diaries as such, though, it’s much more than that. This book will not charm everyone. Which is part of the charm. To quote Heti’s opening lines: “A book about how difficult it is to change, why we don’t want to, and what is going on in our brain.” The book is an enema for your soul.

Alphabetical Diaries is the result of Heti culling 500,000 words from ten years of diaries into a slim text of 60,000 words, with each chapter beginning with a letter of the alphabet. The plot, if there is one, is simply life itself. Forget about causation, linearity, and short paragraphs. Prepare instead for epigrams, maxims, ostensible non sequiturs that are somehow hauntingly germane, and an unabashed self-centeredness that, nevertheless, is obsessed with other people. And if you are repelled by this very description, I invite you to open the book to a random page and see if there is a single sentence that calls out your name, as though you are being addressed by a stranger with startling familiarity, such that you begin to think the stranger is a long-lost friend or a forgotten can of beans. Here’s a choice one: “When you break up with someone, you feel you must have had such incredible powers of self-deception to have gone out with them at all.” Word.

Although competent, admirable women that qualify as Jenny Offill’s “art monsters” do frequently figure in the book, it is the men who stand out. They are brutish, occasionally wise, sexually robust, and sporadically affectionate, by which I mean, they occupy the protagonist’s mind with ferocity faster than you can say variable reinforcement. In other words, the men are basically terrible. I only wish I had trouble relating.

The protagonist’s fixations include a man named Lars, New York, and writerly insecurities. Don’t be surprised to read about brie, blow jobs, or Leonard Cohen. Heti is, probably against her own desire, most emotionally devastating when she talks about men: “I see men with qualities I admire and wish to possess, and I make them my lovers, rather than trying to develop those qualities in myself.” With equal disingenuousness and sincerity, she writes, “I loathe my sexual attraction to men.” And then you have short sentences that call to mind Neuromancer: “Now the sky is the colour of computers.” I was uncomfortably hypnotized by this trio of sentences: “Actually, he doesn’t love you. Actually, he doesn’t want you. Actually, he is looking around the world for another girl, and because of who he is, he will find her and be with her.” Actually, those sentences hurt my feelings.

Given the structure of this book, naturally, the more oft used letters of the alphabet have correspondingly longer chapters and less orthodox letters embody brevity. For instance, the section beginning with the letter z is shortest of all, nothing more than: “Zadie Smith’s husband, who was my favourite person to talk to that night, said he thought a pet was a good release valve for the thoughts and feelings one could not share with one’s partner.” I look at my beautiful dog, think about a man, and sigh audibly: yes, it’s true.