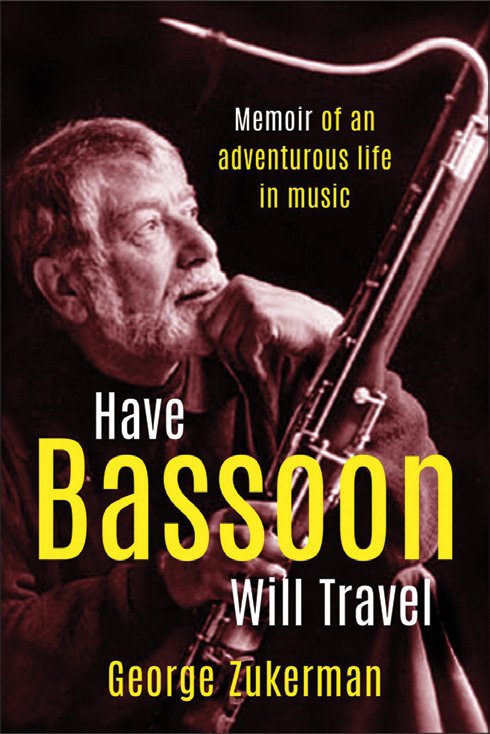

Have Bassoon Will Travel by George Zukerman

Have Bassoon Will Travel: Memoir of an Adventurous Life in Music

by George Zukerman

Ronsdale, 2024; 270 pages. $24.95

Reviewed by Trevor Carolan

In 2005, Ronsdale press brought out Jean Coulthard: a Life in Music. The Vancouver composer’s story, one of the most important in Canadian classical music, was overdue. Then in 2018, Ian Hampton, cellist and co-founder of The Purcell String Quartet— a beloved Vancouver institution — brought out his gossipy jewel Jan in 35 Pieces. Now, with George Zukerman’s late-life memoir we have a cracking trio of books that present a deep dive into the fuller nature of how Vancouver’s — and Canada’s — classical music scene has endured, even thrived into the twenty-first century. Neither a specialist, nor participant in “serious” music like these indomitable

warriors, I’m an unlikely agent to comment on their books or about them. However, as a writer and Spoken Word artist for forty years, like many other west coast arts professionals or former students, I benefitted richly from the commitment of these veterans in their performances and impresario work that brought first-quality concerts to every manner of community venue in Vancouver and throughout BC — shows that otherwise were beyond youthful budgets. They gave us an education, enabling those of us on the way up to benefit from their breadth of classically oriented events, commissioned works and celebrations. Moreover, they expanded our ability to broaden our own work, and to possibly collaborate with different genres of musical artists beyond the levels of sophistication we were accustomed to as jazzers or rockers. Remember, even wild cats like Charlie Parker and Miles Davis honoured old-school classical traditions.

George Zukerman has been a Canadian institution since shortly after WWII. He’s lugged his bassoon — a deep bass woodwind clarinet — coast to coast, north to south, and in nations around the world since realizing there was more to life than simply playing in the Vancouver Symphony. He did that too, naturally, having joined from New York in the early Fifties. Significantly, his first touring gig had been with the St. Louis Sinfonietta, a small orchestra that worked the successful “Community Concert” circuit bringing classical artists of every stripe to smaller towns across the U.S. From this, Zukerman realized the secret of the “organized audience” model, where local organizers hosted advance-paid subscription concerts that are guaranteed risk-free up-front.

While his father was a socialist-minded London journalist with a lifelong contempt for rigid Jewish orthodoxy, Zukerman ironically found himself playing for a year in Tel Aviv with Leonard Bernstein and the Israel Symphony shortly after the country’s founding. Given the Middle East’s current agony, his accounts of those formative times are especially powerful. Returning to Vancouver, he launched his own community concerts, first locally, then around B.C., on to the prairies, Atlantic Canada, and eventually clear across the remote North. What unlikely tales his book has to share!

At its peak, Zukerman’s Vancouver office organized four-hundred concerts a year in seventy-seven communities nationwide, employing dozens of stellar musicians. Zukerman himself played sixty percent of them, travelling by bus, float plane, dog-sled, skidoos, whatever got the music there.

In a maxim that every hopeful artist should learn by heart, he explains how “success [is] built on a mix of professional excellence, audience appeal and touring stamina.” Zukerman also raised the cash for his ventures and his experiences are highly instructive. There was fun too — visiting Inuit villages in the Arctic with an offbeat accordion and bassoon combo, after excerpts from Verdi and Carmen he could count on bringing the house down with a nutty rave-up theme tune from The Simpsons. Yet, like his father, Zukerman the author is compelled to speak his conscience: en route he witnessed clean water problems and lack of transportation in remote Indigenous communities, as well as government promises to fix things that frequently didn’t deliver. But, indefatigably, the music always did, the nonagenarian bassoon boss declares: “It made a difference.”